Wythall has one of the oldest recorded names in the Birmingham area, one which predates the Domesday Book and is found in the Cofton Lease. This Anglo-Saxon contract was drawn up in AD 849 recording the gift of land in this area by Bishop Ealhun of Worcester to King Berhtwulf. Part of the estate boundary runs ufan in Colle; suuae andlang streames in Withan Weorthing, ‘down to the (River) Cole; thence along the stream to Willows Enclosure’.

Wythall has one of the oldest recorded names in the Birmingham area, one which predates the Domesday Book and is found in the Cofton Lease. This Anglo-Saxon contract was drawn up in AD 849 recording the gift of land in this area by Bishop Ealhun of Worcester to King Berhtwulf. Part of the estate boundary runs ufan in Colle; suuae andlang streames in Withan Weorthing, ‘down to the (River) Cole; thence along the stream to Willows Enclosure’.

The current name ‘Wythall’ seems to be flexible, and appears in at least two guises in the Domesday Book as both Warthuil and Wythall. Warthuil, which is

not universally acknowledged as being Wythall, may have been either inaccurately written or transcribed, may derive from an alternative name for Wythall or indeed from a similar nearby place name. The name has been given other interpretations. In Middle English Wyhtehall may be translated as the ‘river-bend hall’, a feasible explanation here. Warthuil may be a mishearing or misreading of wyht hygel meaning ‘river- bend small hill’. It is hard to guess which small hill is referred to in this low and fairly level countryside.

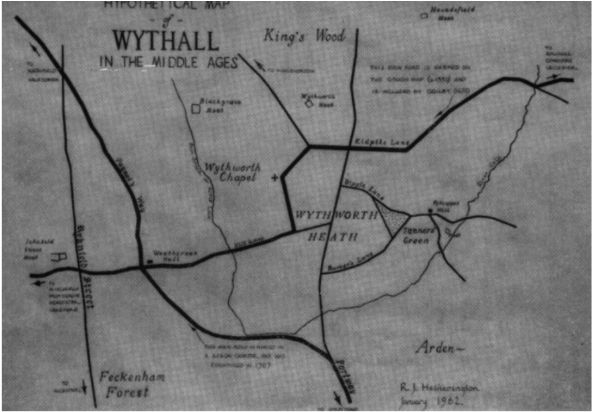

The Domesday Book of 1086 recorded that the king held along with Bemesgrave (Bromsgrove) eighteen berewicks or outlying estates. Amongst these which covered a vast area from Woodcote west of Bromsgrove to Moseley ten miles to the north, Wiieurdc and Hundesfeldc are mentioned, which survive today in the names of Wythwood Cottage and Houndsfield Farms.

Although J. H. Round identified Witeurde as Whitford near Bromsgrove (1) recent opinion has always favoured Wythwaod (2), Nash, the county historian of the 18th century equated the Domesday Warthuil with Wythall whilst W. S. Brassington added his support to this view stating that the name Warthuii meant “the enclosure on the hill”, although the topography of the area would hardly support this, apart from the gentle rise at Tanners Green. (3)

Unfortunately we are given no separate details of the population or individual resources of each berewick as these are described collectively under the parent manor of Bromsgrove. It is reasonable to suppose however that as berewicks their population was quite small, comprising little more than an outlying farmstead with the necessary labour supply to work it. The amount of woodland was considerable, seven leagues by four, but it is quite likely that this represents a total calculation of woodland throughout the manor rather than one extensive tract. Some indication of the inroads made upon the forest is given by the reference to the three hundred cart-loads of wood which annually supplied the salt works at Droitwich. Most interestingly a road called Wychewev in the 15th century and now Silver Street led significantly only as far as Houndsfield. Indicating its purpose as such a supply route to Droitwich. (4)

From contemporary records we learn that the sub-manor of Witeurde was held by the de Wythworth family during the early Middle Ages, but nearby moated Blackgreves seems to have become more important.

Wythwood may have been treated as a separate manor at one time and was held by the de Wythworth family. At his death in 1517 it was recorded that William Sheldon held Wythworth for the Queen, who was the manorial lord of Kings Norton. He bequeathed it to his brother Ralph. In 1633 the manor and its watermill, known as called Kilcupps Mill, was sold by William and Martha Cowper to William Chambers, being sold on in 1711 by Thomas and Edward Chambers to John Holmden. Henry Beighton’s 1725 Map of Warwickshire shows it between Mill Lane and Tanners Green Lanes, and labels it as ‘Kilcop mill olim (ie. formerly) wihtewrthe’.

Richard I is said to have granted Blackgreves to Reginald de Bares, but he soon sold the land to Fulk de Wythworth, went on a crusade and never returned. The king recovered the estate on the grounds that Reginald had broken prison at Feckenham, where he had been detained for larceny. (5)

In 1252 Henry Ill granted Blackgreves to William de Relne of Belbroughton at the annual rent of twenty two shillings. According to 16th century tradition the Bell family acquired the estate from the crown in the 13th century as a reward for military service. (6)

At the time of the Domesday Survey HOUNDESFIELD (Hundesfeld, xi and xiii cent.; Huncksfield, xviii cent.) was one of the eighteen berewicks annexed to Bromsgrove. It belonged to the Crown until the Empress Maud granted it, as the land of Godric de Hundesfeld “with the land of the forester and beadle”, to Bordesley Abbey, probably at its foundation. There is no indication of any movement of the local settlement as sometimes happened when the Cistercians acquired land for their granges. Moreover because of the pre-monastic settlement the Cistercians of Bordesley were not faced with initial clearing activities upon which much of their reputation as great farmers rests. That the Bordesley monks were unable either to pursue fully their early ideals of isolation from the world around them or to acquire a monopoly of property rights in Houndsfield is clear from a series of 13th and 14th century charters preserved by Peter Prattinton, the Bewdley antiquary. (7)

The Baudry family’s tenement was situated near Sims Lane and besides their monastic holdings they held land from Roger de La Feld (or Field). Their family grants describe their holdings and give valuable details of Houndsfield’s medieval agrarian economy and show it to have been organised on the open field system. John Baudry held two selions or strips in Hale furlong which was part of Middle Field, whilst his son, Nicholas, was allotted part of the ‘leyfeld’. By the 14th century some land at Houndsfield was held in severalty, for we find the Baudry family holding land in ‘Wellecroft enclosed by hurdles and a ditch’. According to the royal licence of alienation of 1550 whereby Houndsfield was granted to John Arrowsmith. it appears that all the Bordesley land was enclosed. In the Valor Ecclesiasticus, the manor or grange of ‘Houndesfelde with Norton was let at a rent of £10 0s 8d per annum.

Between Domesday and the late 13th century it has been estimated that the population grew on a national scale by at least two and a half times (8) It is therefore not surprising to find that this period is marked by considerable extension of the area under cultivation on the margins of existing settlements and by colonisation of new areas hitherto untouched. This expansion of cultivation into isolated areas of the parish is reflected by the surnames in lay subsidy rolls and a mid 13th century rental indicating the extent of colonisation beyond the two Domesday berewicks. Osbert le Sele (Seals Green Farm) and Emma del Holies (Hollywood) appear in the Kings Norton Rental, whilst in the 1275 Subsidy Roll (9) we find Richard de Kyngeswode, John de la Strete (referring to the Roman Ryknield Street) and Ralph and William de Grymesput at Grimpits Farm. In the main, colonisation took the form of severalty assarts won from the waste and forest, resulting in early enclosed farmsteads and reflected in such fieldnames as Stocking at Leasowes Farm, denoting a piece of ground cleared of stumps, or the Ridding at Kingswood referring to the ridding of the land of its trees and undergrowth.

A distinctive feature of many of these early enclosed farms is the existence of a moat around the house, now very often only fragmentarily preserved. The material dug from the moat, which was usually between 20-35 feet wide, was often used to raise the level of the island above the surrounding land, thus providing a dry house platform. The best preserved local moated site is that around Blackgreves Farm where there are traces of an outer moat on the south-west, but there are fragments at Pool House, Wythwood Cottage, Bleakhouse, Goodrest and Headley Heath Farms. Moving slightly further afield, The National Trust owned Old Moat House in Earlswood is considered the oldest moated (with water still in it!) manor house left in the county. (10)

Although of little strategic value against attack, in forest areas a moat would provide some degree of protection especially against the depredation of deer or wild animals. Although nationally this colonisation movement had petered out by the mid-14th century due to successive plagues and economic recession, it appears to have been resumed in part locally by the end of the century and continued into the 15th. An inquisition post mortem made of the property of “Hugh de Belne of Kynges Norton” in 1318 describes Blackgreves as “a certain capital messuage which is worth nothing yearly because it is wholly ruined” with sixty acres under the plough and another two held front the bishop of Worcester in Alvechurch – probably adjoining land just over the parish and manor border, the Bell brook. (11)

By 1362 the property had been repaired and the amount of arable had been extended to one carucate, generally reckoned to be about 120 acres. (12) There was also 10 acres of meadow, valuable for its hay crop and livestock pasture after the July mowing and the same acreage of woodland, giving a total of 140 acres; a figure which corresponds well with the 139 acres of the 1843 Tithe Award.

As part of the royal manor of King’s Norton the more prosperous tenants or villein sokemen enjoyed several privileges and immunities not available on the ordinary lay estate; the right to leave their tenements at will, safeguard against eviction or increase in services owed and the right to sell their produce in any market in the king’s dominions”. (13)

Requiring a labour force to work his lands a tenant of the crown either depended on hired labour or would acquire his own sub-tenants from amongst the lower orders of peasant society, who in turn might hold small parcels of land in return for services. Unfortunately the lowest levels of medieval society are extremely difficult to trace in our sources although we catch occasional glimpses of them through court rolls and lay subsidy rolls. The latter were assessed on the value of movable goods owned and thus enable us to compare relative prosperity within the whole parish. One is immediately struck by the wide variations of peasant wealth as reflected in the 1275 roll, although in reality they must have been even wider than the documents suggest as the very poor are hidden through exemption.

Moreover our sources tell us very little about the settlement pattern of the parish beyond the distinctively named, early enclosed farmstead. Whilst some labourers may have lived within their employers’ court, there is some evidence for the existence of nucleated settlements, if only of hamlet size, within the parish. One such centre was Gorssawe where four taxpayers were living in 1275. (14)

It continued to expand two centuries later for in 1475 we hear that William Fylde of Gorshawe has built himself a house of two bays on the lord’s soil but the King’s Norton court ordered him to remove it by Michaelmas. (15) Gorssawe is probably represented by the present Wythall village along the old Alcester road, (16) whilst another small nucleated settlement has been postulated at Tanners Green. (17) This was known as Withwood Green as late as 1822 (18) and its green, at the focal point where four ancient lanes from the west and south meet, survived well into the present century. To the south towards the River Cole and Tanworth lay another moated enclosure around the modern ‘Moat House’, but whose function is uncertain. It may represent a very early moated homestead, or more probably, was associated with the manorial watermill which stood near here. Henry Beighton’s Map of Warwickshire of 1725 marking it between Mill and Tanners Green Lanes, describes it as “Kilcop mill Olim (formerly) wihtewrthe”, suggesting its earlier history. The Kilcup family flourished at Wythall in the 16th century, but the watermill which they acquired at Tanners Green was of early medieval origin. (19)

As well as the watermill there was also a windmill which was situated on the manorial waste, Wythworth Heath, which survived until the 18th century enclosure and separated the Cole valley hamlet from chapel and hall. To take full advantage of the wind the mill was raised on an earthwork mound 5’ 6” high and 80 feet in diameter dug from a surrounding ditch. Its tump remained until 1967, but has since been swept away by roadworks. (20)

One of the most significant and interesting events in the manor of King’s Norton during this period was the ugly incident caused by Roger Mortimer’s enclosure of King’s Wood. The Mortimers had gradually obtained vast possessions in King’s Norton until, in 1317 Edward II granted to John Mortimer the manors of Bromsgrove and Norton for a rent of ten pounds to he paid into the royal exchequer. In the early 1320’s Roger Mortimer, Earl of March, caused part of the common land shared by the inhabitants of King’s Norton, Solihull and Yardley to be enclosed with a dyke. (21) The inhabitants, having thereby lost their ancient rights, filled up the ditch “as was lawful the earl obtained a plea of trespass against them whereupon they were convicted by jurors dwelling far from the said land who had been put upon the panel by Richard de Hawkeslawe, the earl’s steward, then sheriff of the county.” (22) The tenants “did not dare appear to challenge the jurors of the inquisition (held at Bromsgrove) for fear of death and the power of the earl, they were convicted and adjudged to pay £300 to the earl for damages.” However the money was not paid immediately and on the accession of Edward III Mortimer was seized as a criminal and imprisoned in Nottingham Castle in 1328 and directly executed at Tyburn. The tenants of the three parishes humbly petitioned the crown for a reduction of the fine which was agreed upon; “in respect of this sum the said men by petition before the king and his council in Parliament have prayed that, whereas the same is now required of them for the king’s use by reason of the earl’s forfeiture, he would be willing to show them special favour in the matter; and under the circumstances he pardons £286 13s. 4d. out of the said £300 so as they satisfy the remaining twenty marks as the exchequer”. (23)

Such a plucky uprising of the inhabitants of King’s Norton serves to show their awareness of their rights of common pasturage with their resultant collective action, whilst the story itself emphasises the essential link between national and local history.

S J Price

- VCH Worcestershire vol. I p. 285

- I. J. Monkhouse in H. C. Darby and I. B. Terrett Domesday Geography of Midland England (1954) p. 221 and R. J. Hetherington in Wythall and St. Mary’s Church (1962) p. 5

- Notes on the history of King’s Norton p. 9 BRL 505240).

- Peter Prattinton Manuscript Collection of Parochial Notes and Illustrations vol. VI p. 103 (i468 in Society at Antiquaries Library, London.

- VCH Worcestershire vol. III p. 186.

- W. 11. Buchanan-Dunlop ‘The Testament of William Bell at. Belne 15B7’ In TWAS vol. XXXVt (1949) p. 20.

- Prattinton MSS vol. VI pp. 112-113.

- J. Z. Titow English Rural Society 1200-1350 (1969) p. 71.

- Lay Subsidy Roll for the County of Worcester c. 1280 ed. J. W. Willis Bund & J. Amphlett (WHS 1893) pp. 66-68; King’s Norton Rental PRO Special Collections 11/717.

- The moat at Wythwood Cottage Farm is mentioned by R. J. Hetherington ‘Can Wythall be saved from town planning’ in The Redditch Indicator 7.8.1959. For the rest see below pages 46-50.

- The lnquisitiones Post Mortem for the County of Worcester cd. J. W. Willis Bund part Ii (WHS 1909) p. 107.

- Calendar of Close Rolls 13410-64 p. 313

- W. Hutton A History of Birmingham (2nd ed. 1783) p. 33.

- Willis Bund & Amphlett op. cit.: (1893) p. 67.

- B. K. Field ‘Worcestershire Peasant Buildings in the Later Middle Ages’ in Medieval Archaeology vol. IX (1965) p. 126.

- The Court Rolls of the Manor of Bromsgrove and King’s Norton ed. A. F. C. Baber (WHS) 1963: John Felde of Gorshaw fined 4d. in 1499 for failing to cleanse the banks of his property between Shaw broke and Wythworth bethe. The name survives in Gorsey Lane.

- B. J. Hetherington in Wythall and St. Mary’s Church (1962) p. 6.

- J. B. Harley Christopher Greenwood, county map-maker and his Worcestershire map of 1822 (WHS 1962

- W. Dugdale Antiquities of Warwickshire (1730 ed.) vol. II p. 448 dates a MS temp. Henry 111/ beginning Edward I mentioning Wihtewrthemilne. When the Moat House was built c, 1930 two mill Stones and a quantity of rubble were found.

- Certificate for the sale to John Taylor of the Manor of King’s Norton 18-10-1804 PRO Crest 34/20U Schedule no. 55 describes the site as “Windmill Bank.” Rescue excavation reported briefly in Excavations Annual Report 1966 (Ministry of Public Building & Works) p. 8.

- According to Hutton op. cit. (1783) p. 372 the dyke known as Mortimer’s Bank survived as an earthwork at least until the 1772 enclosure. It ran for nearly a mile in length at Kingswood “two hundred yards east of the Alcester Road”.

- Hutton claims that “the inhabitants threw down the fence and murdered the Earl’s bailiff”.

- Calendar of Patent Rolls 1330-34 p. 268. Page 16